Two numbers are randomly chosen between \(0\) and \(c\). They are \(X = 3.6\) and \(y = 5.4\). Consider the following estimates of \(c\): \[\begin{align*}

U &= X + Y \\

V &= \max(X, Y) \\

\end{align*}\] Which estimate should we choose, and why?

Solution

Let \(X, Y \sim^\iid U(0, c)\). Then, to determine the mean, bias, variance and MSE as the following,

\[\begin{align*}

\E{U} & = \E{X + Y} = c \tag{U.mean} \label{eq:u-mean} \\

\bias{U} & = c - c = 0 \tag{U.bias} \label{eq:u-bias} \\

\Var{U} & = \Var{X + Y} = \Var{X} + \Var{Y} = \frac{c^2}{6} \tag{U.var} \label{eq:u-var} \\

\mse{U} & = \Var{U} + \left( \bias{U} \right)^2 = \frac{c^2}{6} \tag{U.mse} \label{eq:u-mse} \\

\end{align*}\]

To find out the measures for \(V\), we first need to determine the distribution of \(V\). Fortunately, we know that it is the order statistics. Recalling from previous chapter, we have discussed that the general formula for order statistic (\(n = 2\)) is, \[\begin{equation*}

f_V(v) = f_{U_2}(v) = \frac{2!}{(2 - 1)!(2-2)!} F(v)^{2 - 1} \left( 1 - F(v) \right)^{2-2} f(v) = 2F(v)f(v) = 2 \left( \frac{v}{c} \right) \frac{1}{c} = \frac{2v}{c^2} \; \text{(for $v \in [0, c]$)}

\end{equation*}\]

\[\begin{align*}

\E{V} & = \int_0^c \frac{2v^2}{c^2} \, dv = \frac{2}{c^2} \left[ \frac{v^3}{3} \right]_0^c = \frac{2c}{3} \tag{V.mean} \label{eq:v-mean} \\

\bias{V} & = \frac{2c}{3} - c = -\frac{c}{3} \tag{V.bias} \label{eq:v-bias} \\

\E{V^2} & = \int_0^c \frac{2v^3}{c^2} \, dv = \frac{2}{c^2} \left[ \frac{v^4}{4} \right]_0^c = \frac{c^2}{2} \\

\Var{V} & = \E{V^2} - \left( \E{V} \right)^2 = \frac{c^2}{2} - \left( \frac{2c}{3} \right)^2 = \frac{c^2}{18} \tag{V.var} \label{eq:v-var} \\

\mse{V} & = \Var{V} + \left( \bias{V} \right)^2 = \frac{c^2}{9} + \frac{c^2}{18} = \frac{c^2}{6} \tag{V.mse} \label{eq:v-mse} \\

\end{align*}\]

Therefore, we can clearly see that \(V\) is biased from \(\eqref{eq:v-bias}\). However, the MSE is actually the same as shown in \(\eqref{eq:u-mse}\) and \(\eqref{eq:v-mse}\). Therefore it is relatively hard to say which one is better. We see that \(U\) is:

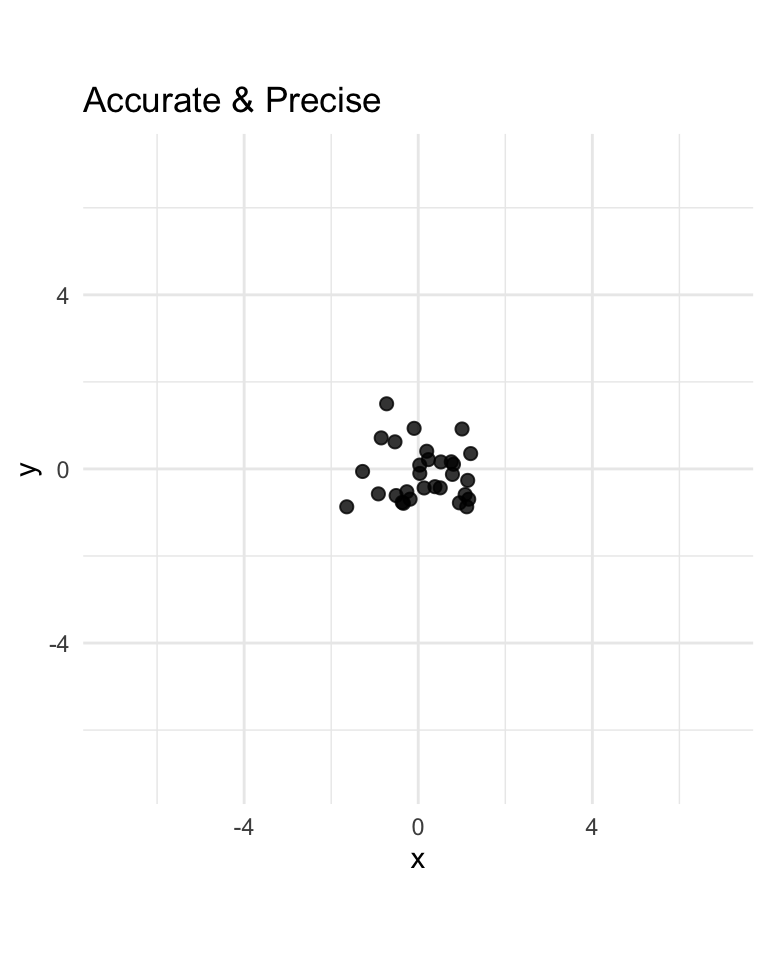

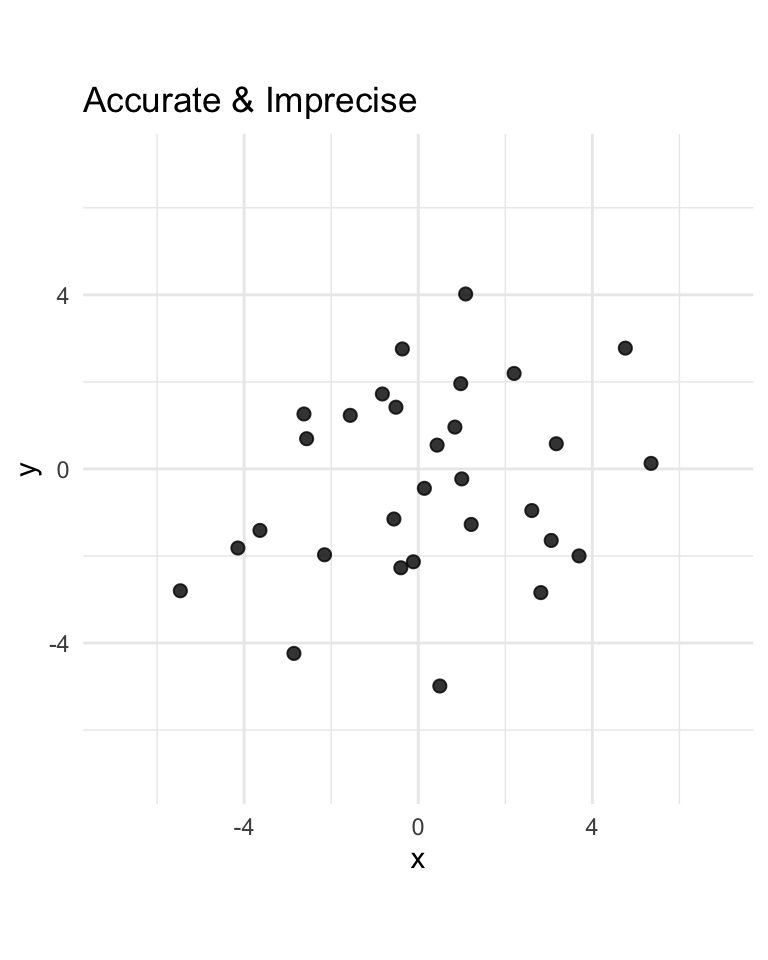

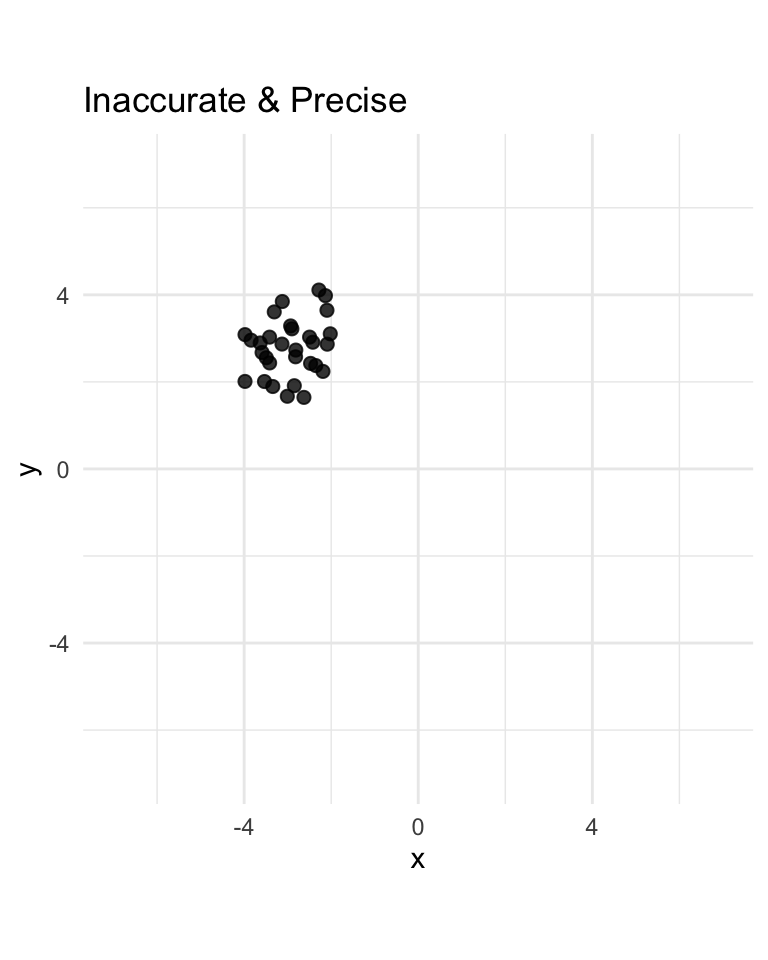

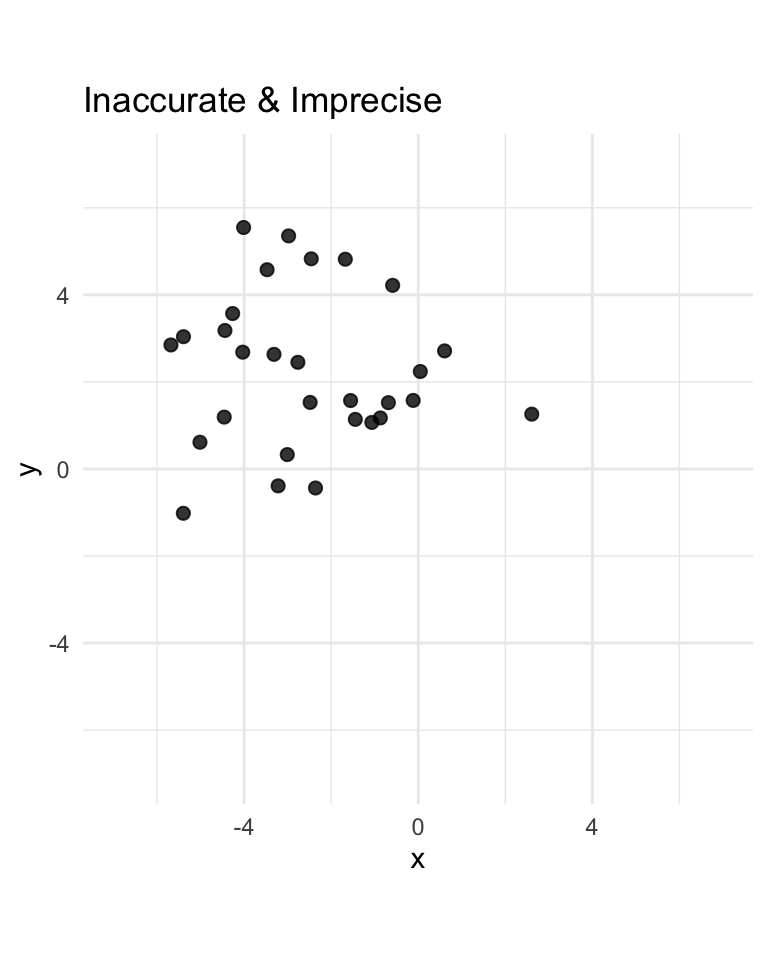

- more accurate than \(V\) (non-bias vs bias)

- less precise than \(V\) (since \(c^2 / 6 > c^2 / 18\))

- overall about as good as \(V\) (since \(c^2 / 6 = c^2 / 6\))

Since \(U\) is unbiased and \(V\) is not, we choose \(U\) as the better of the two estimators. Does this mean that the estimate \(V\) is useless? No. We can make use of \(v\) as a starting point (or basis) for constructing an estimate that is better than \(U\). Observe that \(\E{V} = 2c/3\). This implies \(\E{3V/2} = c\). So we define \(W = 3V / 2.\) This is another estimator of \(c\) to be considered. Now, what is the variance of \(W\), \[\begin{equation*}

\Var{W} = \left( \frac{3}{2} \right)^2 \Var{V} = \frac{9}{4} \cdot \frac{c^2}{18} = \frac{c^2}{8}

\end{equation*}\] Therefore, we obtain the MSE as \[\begin{equation*}

\mse{W} = \Var{W} = c^2/8

\end{equation*}\]

Now, we see that \(W\) is:

- just as accurate as \(U\)

- more precise than \(U\)

- overall better than \(U\)

We conclude that \(W\) is best of the three estimators. So our best estimate of \(c\) is \(W = 1.5 \max(X,Y)\), our second best estimate is \(U = X + Y\), and our third choice would be \(V = \max(X, Y)\).